by Sam L. Savage

Shaun & Karen Doheney

WSC 2019 was more than I had hoped for! I co-chaired a track on Risk Analysis with David Poza (pictured below), ProbabilityManagement.org was involved in a number of presentations, and we had a booth in the exhibitor’s area. Shaun Doheney, our Chair of Resources and Readiness Applications, and I gave several workshops on probability management, and he and his wife Karen generously assisted with logistics. I also want to thank Melissa Kirmse for helping get the papers submitted, and Mary Claire Meijer for managing the track details for me and David.

Doug Hubbard gave a paper on his latest Multi-Seed Pseudo Random Number Generator that can ensure enterprise-wide coherence among networked simulations.

And Tom Keelin presented our joint work with Lonnie Chrisman on solving the long-standing problem of calculating sums of IID Lognormal variables. You won’t want to miss Tom’s presentation on the role of Metalogs in Bayesian Inference at our own Annual Conference in San Jose on April 21 - 22 .

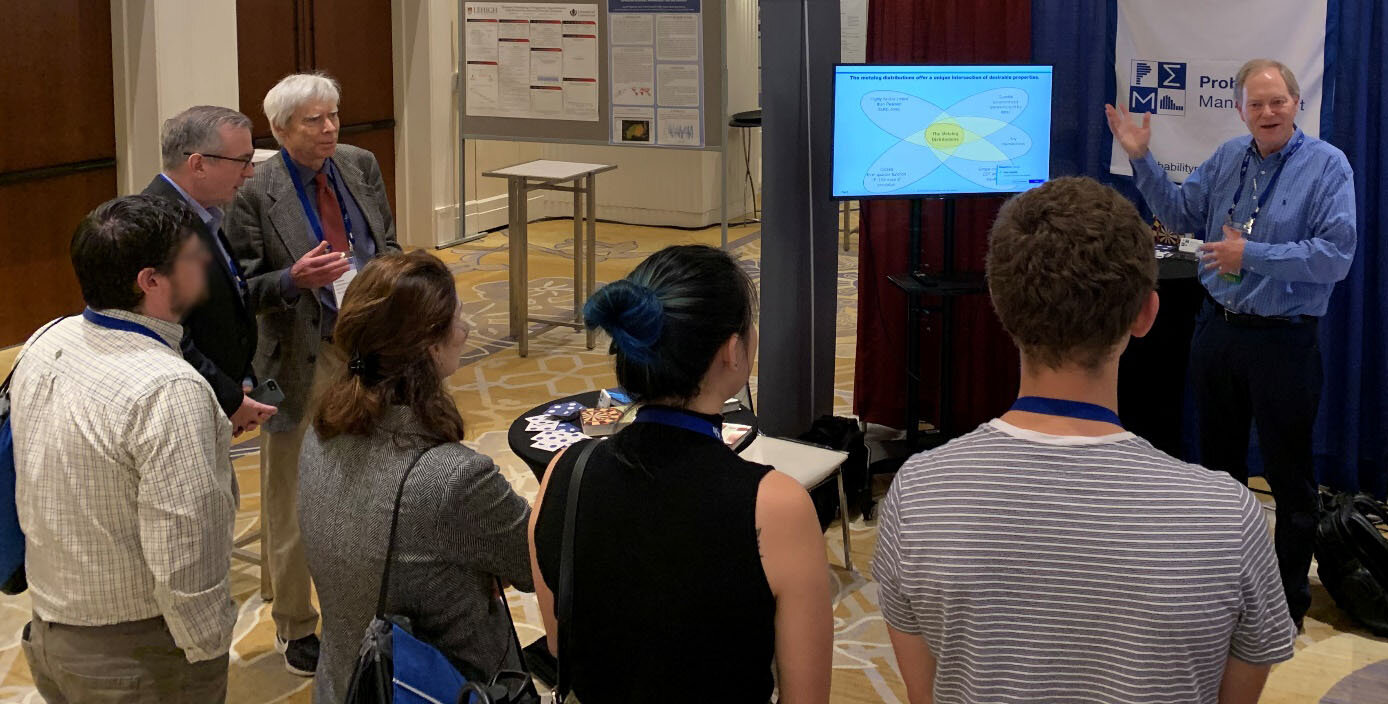

But for me and Tom, the highlight of the conference was meeting Larry Leemis, a prominent professor of Mathematics and Operations Research at William & Mary. A few months ago I had been shown Larry’s interactive chart (below) that displays the mathematical relationships between probability distributions. Shortly before the conference I realized that Larry might be attending WSC and suggested a meeting with Tom. Not only was Larry at the conference, but he had brought several OR graduate students with him. The resulting interactions were stimulating and of particular benefit as we explore the ultimate role of Metalogs in the world of theoretical probability distributions.

Sam Savage and David Poza

Doug Hubbard, Sam Savage, and a group of Professor Larry Leemis’s graduate students from William & Mary at a presentation on Metalog Distributions by Tom Keelin.

Professor Leemis’s chart of Univariate Distribution Relationships

© 2019 Sam Savage