Beware of the Pilot Induced Oscillation (PIO)

by Sam L. Savage

Recently I have been struck by the similarities between managing the pandemic and flying a plane. In both situations you are responding to lagging indicators. Learning about this phenomenon through flying taught me to connect the seat of my intellect to the seat of my pants, which today I call limbic analytics.

In the late 1970s I learned how to fly gliders over the soybean fields just west of Chicago, and it was one of the few things in life that was as good as I thought it was going to be. But it was not easy.

Having built and flown model planes as a kid, and having studied physics in college, I expected flying to come naturally to me. It didn’t. The seat of my intellect and the seat of my pants were often at odds with each other, and they had to reestablish mutual trust a few thousand feet above the world in which they had teamed up to teach me to crawl, walk, run, swim, and ride a bike.

This mind/body link is described in detail in my book The Flaw of Averages in Chapter 5: The Most Important Instrument in the Cockpit. And because of the pandemic and the lagged indicator problem, it has recently been front of mind for me.

You can’t learn how to ride a bicycle by reading about it, and the same is true for flying. My friend Ron Roth and I created a flight simulator where you can experience this lesson in limbic analytics for yourself. In any plane, if you fly too slowly, you will stall and lose control, and if you fly too fast, you will rip the wings off. Not surprisingly, these unfortunate possibilities weigh heavily on the mind of the student pilot, who tends to focus their gaze on the airspeed indicator. They shouldn’t.

In a glider, or normal airplane at constant power setting, the speed depends on the pitch up or down of the nose. Imagine that you are creating an on-demand roller coaster in the sky just in front of you. Pull back on the stick and the nose points up, slowing you down. Push forward and the nose points down and the speed picks up. The problem is that because the speed lags the pitch of the nose, the novice pilot with their eye on the airspeed indicator tends to make a growing set of overcorrections, which can lead to loss of control (see video).

This is known as pilot induced oscillation or PIO, and the solution is to NOT look at the airspeed indicator, but to focus on the angle of the nose above the horizon, which is a leading indicator of airspeed. That’s why the most important instrument in the cockpit is the windshield!

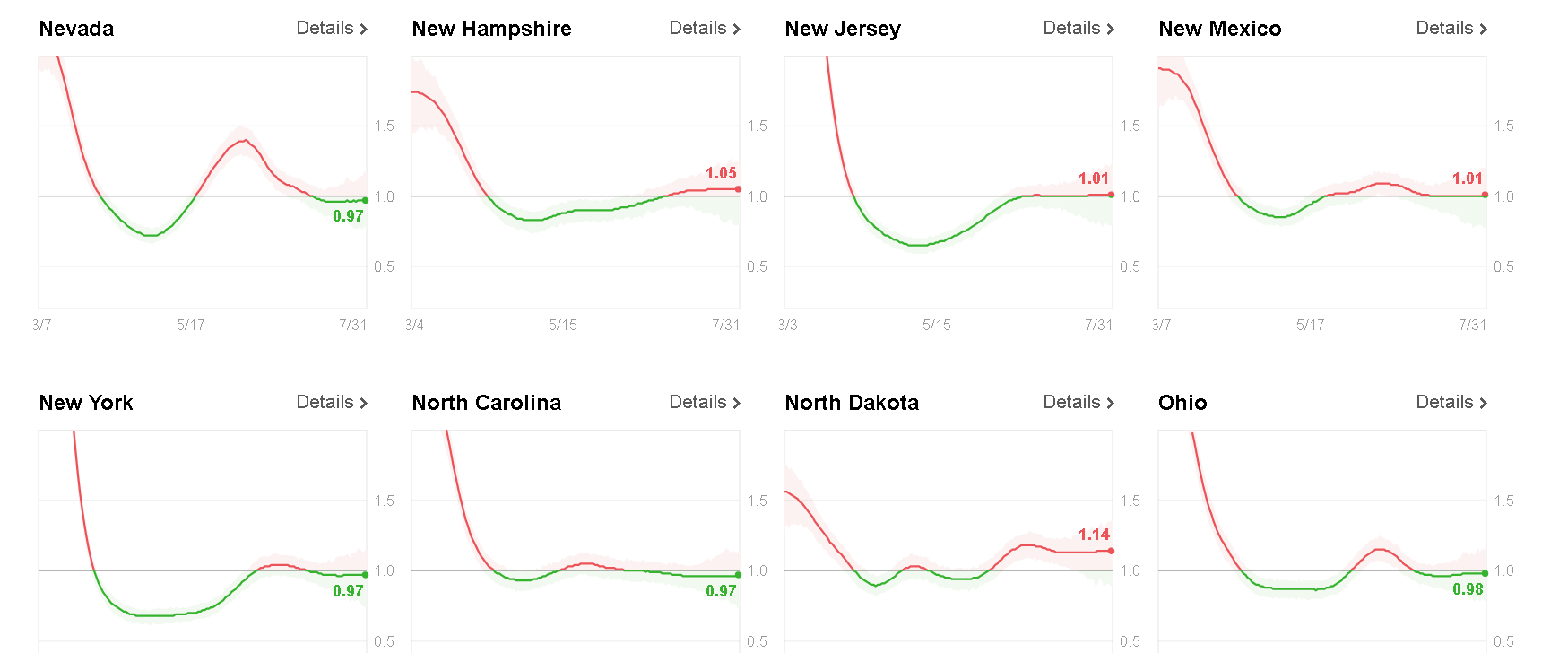

But, where were we? Oh yes, the pandemic. The death rate is lagged from the ICU patients, which is lagged from those admitted to the hospital, which is lagged from those infected, which is lagged from the infection rate, which we can’t really see. So, this is not an easy plane to fly. If you don’t believe that it is difficult to maintain control through lagging indicators, try flying our simulator in various modes and compare the graphs of your attempts to control the speed to the graphs of the infection rates from rt.live, a website that plots current infection rates by state. You will find an uncanny resemblance.

Graphs from rt.live

And how about flying the economy? It’s even harder! Mathematically, contagion growth is a piece of cake compared to an economy. Oh, and how about influencing human behavior in the face of unknown threats? That’s harder even than the economy, and all three of these unstable airplanes need to be flown in tight formation.

The pandemic equivalent of the angle off the horizon is the infection rate. The economic equivalent involves manufacturing, inventory levels, housing permits, etc. Public behavior is traditionally influenced by the news media and politicians who are often at odds.

So, what can our nonprofit do to help?

Even without political strife, the communication of uncertainty between epidemiologists, economists, reporters, and politicians is usually reduced to average outcomes, as in the Flaw of Averages. Our nonprofit has now brought the war on averages to the pandemic by helping the stakeholders unambiguously communicate the uncertainties faced in their own domains. See our previous blog posts:

The Value of Information About COVID-19: What Will the Information We Learn in the Next Two Weeks Be Worth?

A Combination of the Coronavirus and the Flaw of Averages Can Drive You Nuts

If you want to learn more about our efforts, email us at info@probabilitymanagement.org.

© Copyright 2020 Sam L. Savage